The Loss of Justice Scalia is a Loss for Religious Freedom

Stanley Carlson-Thies

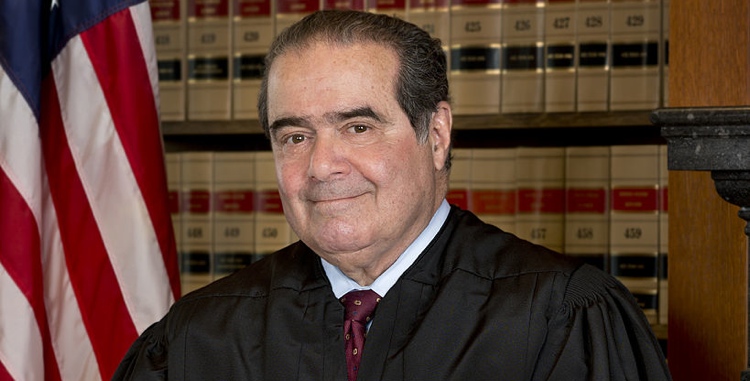

Tributes to US Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, who died suddenly on February 13, 2016, have been flooding in, including from some who were his intellectual and judicial opponents. He was a rare member of the Supreme Court, a rare public servant, one whose clarity, carefulness, and persistence helped significantly reshape thinking and practice on important public matters.

Two brief notes on his Supreme Court decision-making. In his sharp dissent to last summer’s Obergefell decision, by which the Court mandated same-sex marriage throughout the United States, Justice Scalia focused on what he regarded as the Court majority’s substitution of its own normative view about marriage for the citizens’views, which were being expressed state by state through the legislative process. But before those comments, he said he joined “in full”the dissenting opinion of Chief Justice John Roberts.

Roberts also charged that the Court majority had “enacted their own vision of marriage”as what the Constitution supposedly required. But he also sharply criticized the Court’s action for its negative consequences for religious freedom. When states enacted same-sex marriage themselves, he pointed out, in every case they also adopted specific protections for religious organizations and persons whose convictions do not support marriage redefinition. While the Court majority—weakly—took note of the need to protect religious dissenters, the Chief Justice pointed out that is not the competence of any court to create religious accommodations as can lawmakers. By requiring same-sex marriage by court action, the Supreme Court gave us all a religious freedom problem. We do not yet know how this problem will be resolved.

Justice Scalia is noted especially for a different religious freedom decision of the Supreme Court, Employment Division v. Smith (1990). This was a case about whether religious freedom protected native Americans who used peyote, a banned substance, in a religious ritual. In an extremely important opinion, Justice Scalia wrote for the Court majority that, while it would be a violation of the Constitution for a government to pass a law specifically to impede religious exercise, it was not a constitutional violation if a generally applicable law only impaired religious exercise by collateral damage. The Constitution permitted the government to accommodate religious freedom under such a general law, but it did not require such an accommodation.

And yet, because religious conviction often leads people and organizations of faith to act, or to refrain from acting, in ways different than other citizens and organizations, general laws not designed to curtail religious exercise can very easily do so. A simple example: a prohibition on the sale and use of alcohol may be intended to curb drunkenness and drunk driving but will just as surely undermine the use of wine in religious ceremonies as if the legislature had specifically targeted religious rituals. And so Justice Scalia’s carefully reasoned but inadequate opinion in Smith quickly called into action a very broad coalition of religious and civil rights leaders and organizations, and within three years Congress, acting nearly unanimously, adopted the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), which President Bill Clinton signed with his very strong endorsement on November 16, 1993.

RFRA was designed to restore the religious freedom interpretation that preceded the Smith decision, and it gives us the following carefully designed framework:

When a religious person or organization believes that its religious exercise has been substantially burdened by a law of general application, it can require the government to defend its law in court. If the court decides that there is in fact a “substantial burden,”then, to uphold the application of the law to that person or organization, the government has to demonstrate both that the law expresses a “compelling government interest”and that the law has chosen the “least restrictive”means of achieving that interest. If not, the law is inapplicable to that person or organization.

For example, in the Hobby Lobby case, the Court determined that the contraceptives mandate of the health reform law imposed a substantial burden on the religious exercise of the Green family, which sought to follow its pro-life convictions in operating the company. And then the court found that, even if the federal government had a compelling interest to maximize women’s access to contraceptives, including the abortifacients to which the Greens objected (the Court didn’t rule if it did or did not), it had not chosen the method to achieve that interest that was the least burdensome on the religious convictions of the Greens (and others like them).

So we have RFRA because of Justice Scalia, a statute that strongly protects religious freedom, as a consequence of an interpretation of the First Amendment that weakened its religious freedom protections. But recall that in the Smith decision. Justice Scalia said that the legislature could legitimately strengthen the protection of religious exercise, even if the Constitution did not mandate that stronger protection.

And yet, although his decision in the Smith case was unintentionally damaging, there is no doubt that Justice Scalia regarded religious freedom to be a bedrock principle of the US Constitution and of the United States political community. His rulings about religious issues and about government and civil society (almost always) safeguarded the freedom of religious organizations and religious persons. His clear and vigorous mind and voice will be much missed in Supreme Court jurisprudence.

On the background, support for, and meaning of the federal RFRA, read the brochure published on RFRA’s 20th anniversary by the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty.