Can Federal Contractors Continue to Staff on a Religious Basis? Two briefings.

Stanley Carlson-Thies

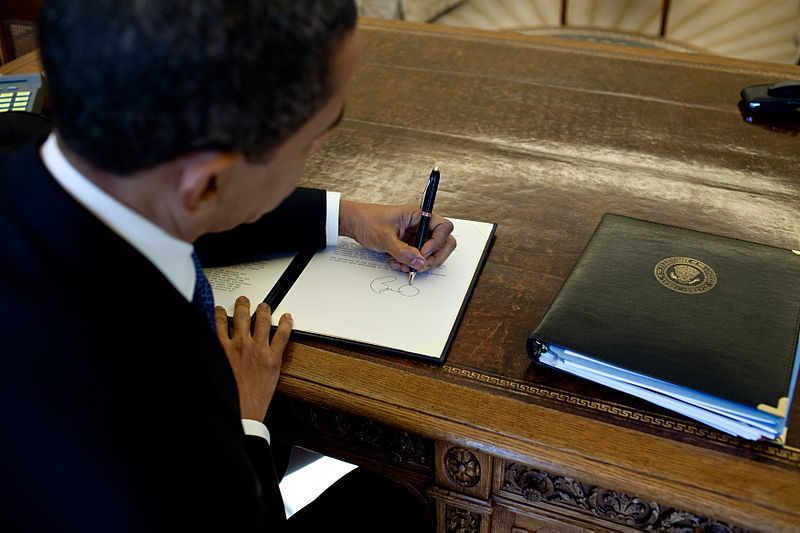

On June 17-18, 2015, Carl Esbeck of the University of Missouri Law School presented two Washington DC briefings on the right of religious organizations to consider religion in staffing, in the wake of President Obama’s Executive Order forbidding job discrimination on the bases of sexual orientation and gender identity by federal contractors and subcontractors.

The question arises because, while President Obama did not exempt religious organizations from the new nondiscrimination requirements in federal contracting, he also did not eliminate the existing religious exemption in the contracting rules. That exemption is like the exemption in the general federal employment nondiscrimination rule (Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act) and permits religious organizations to take account of religion when they make staffing decisions.

And the question arises because, while the exemption permits employment decisions based on religious considerations, it does not exempt religious organizations from the requirement not to discriminate based on sex, race, national origin, sexual orientation, gender identity, etc. And as part of considering religion when making staffing decisions, many religious employers take account of conduct and not just formal beliefs—they are seeking employees who exemplify in their lives the religious commitments of the organization (or, at a minimum, employees whose conduct and expression do not undermine those religious commitments). Thus many religious employers have conduct requirements, which often include religiously based standards concerning marriage and sexual relationships.

As it turns out, the religious staffing exemption in the federal contracting rules (and in Title VII) is expansive enough to go beyond mere religious formality: employers rightly can ask that an employee or potential employee not simply state agreement with the employer’s religious beliefs and standards but manifest agreement in how they conduct themselves. But “taking account of religion” when making staffing decisions cannot be arbitrary nor a pretext for making what is actually an illegal discriminatory decision.

Here then is another reason for religious organizations to be systematic, transparent, and careful in connecting together their religious convictions, their policies, and their practices.

And yet, because employer decisions are subject to second-guessing by disappointed job seekers, administrative officials, and judges, Congress would do well to specify more clearly that the religious decision-making that is protected by the religious staffing freedom is not narrowly confined by the prohibitions on discrimination on the bases of sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity. Religion is not mere belief or talk but extends to assessments of how people act and to convictions about relationships.

[Professor Esbeck’s briefings are being developed into an article that will be announced by this eNews when available.]